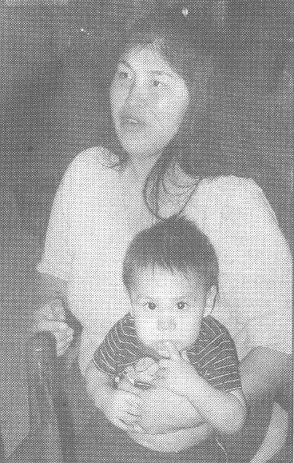

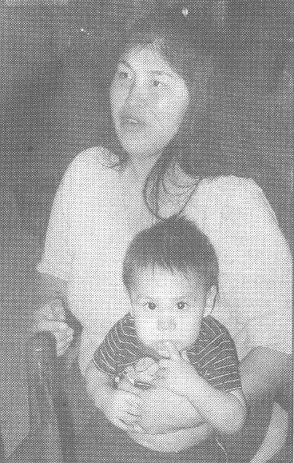

Marilyn Chase Jones with her youngest son, Josiah, in her North Pole home

Marilyn Chase Jones with her youngest son, Josiah, in her North Pole home

Heartland Magazine, Fairbanks, Alaska, January 4, 2004

Judy Ferguson

Regeneration after seeing the light

DELTA JUNCTION--Most of us live with the capacity for destruction. Marilyn Chase Jones. Alcohol--related accidents, violence and death surrounded her while she was growing up in Anvik.

Marilyn Chase Jones with her youngest son, Josiah, in her North Pole home

Marilyn Chase Jones with her youngest son, Josiah, in her North Pole home

|

I first met Marilyn in 1975, when my family's canoe pulled up to Anvik. Standing on the Yukon River bank was Ken Chase, Marilyn's father and an eighth- place finisher in the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race. His daughter, Marilyn, then 11, was cutting fish for their dog ream. Ken's wife, Katherine, had left when Marilyn was 3. Ken raised his children alone but had lost a son to a Yukon River boating accident.

In December, Marilyn, now a 39-year-old woman living in North Pole, softly told her story of great darkness and the light she had found, appropriate to the Christmas season.

As she had grown up, villagers often drank homebrew, toxic in its high alcoholic content, Marilyn said, "The things people would never ordinarily do, after drinking homebrew, they did." Marilyn's father, enforced a nightly curfew for his children. Marilyn festered over the "unfair treatment." When she was only 15, she moved away from home to Grayling, fueling her rebellion further with alcohol. At a party, she met her first husband, and in 1984 her first daughter was born, followed by a son a year later. On Christmas morning a few months later, she said she woke her husband, saying, "The police will be here soon. Last night you stabbed a man 17 times."

After initial incarceration, Marilyn's husband was released on bail. During the subsequent days, Marilyn's third child was conceived. When the second daughter was born, her father was sent to prison. Marilyn struggled alone with three small children and ultimately met a new boyfriend. Through that relationship, two more children were born. A baby girl, born with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, was adopted at six months. When Marilyn realized she was pregnant again, she quit drinking.

But after the birth of another daughter, hers and her boyfriend's days were blurred once again with alcohol and punctuated with violence. Neighbors reported suspected abuse of the children. One day, while the children were sledding, Social Services workers took Marilyn's children away, kicking and crying. Marilyn's heart was torn, but she refused treatment. Rather, she met a young man from Minto and conceived her second son. Again she was in a relationship in which drinking was a priority. With a wry look on her face, Marilyn commented on the power alcohol had over her life. "I always knew liquor was called spirits."

In 1996, Marilyn's sister, Carolyn, became a Christian and began praying fervently for Marilyn. At about the same time, Marilyn had a dream that her late grandfather, William Chase, was beckoning her to return to church. When her baby son was 8 month old, his intoxicated father accidentally dropped the baby on his head, Marilyn said. Neighbors again reported the family; the police handcuffed Marilyn, and the baby was taken away and placed with another family through a tribal governmental agency.

Marilyn and her boyfriend began stealing liquor, sleeping in tents in a "tent city" populated by inebriates in downtown Fairbanks.

During an attack of anxiety, Marilyn suddenly felt as if she were going to die. She checked herself into a detoxification center. She recalled crying out, "God in heaven, please help me. I can't do this by myself." "I felt a calm come over me," Marilyn said in her soft voice. "I cried; I read my Bible. I went to sleep; I slept good. I got up. I smoked a cigarette; I started retching. Cigarettes, alcohol all suddenly made me sick."

For the next two months, Marilyn tried to get her youngest son back. But, she said, "the Minto tribal government said, 'No, you must go through treatment and document it.' I got on the list for the Minto Recovery Camp.

"Again," Marilyn said, "I briefly got off track-with my son's father. Then, I told my sister's husband, a pastor, how I wanted to get my kids back.

'Marilyn,' he told me gently, 'you have to make a stand. God will honor you.' So I told my son's dad, 'You got to leave; I am going to serve God.'"

Marilyn said, "Even though I did everything Social Services asked, they and the tribal government wouldn't return my children to me. All my rights had been terminated. Again, my brother-in-law said to me, 'Marilyn, you can't do it yourself. Let God do it.'

A couple of my children had been legally adopted. But after I took a stand-one by one-I began getting my children back. That had never before happened. When all my children had returned, I asked the Lord, 'Let me have a husband who loves You as much as I do, who doesn't drink, who has a sense of humor and loves the out-of -doors. Over the years, my sister had told me of an American Pueblo/Norwegian man who was teaching my kids in Holy Cross, Robert Maxwell Jones."

Ultimately the two met and married in Fairbanks in 2002. "The Lord brought us together," Marilyn said.

Today, Max, Marilyn, her children and their new baby, Josiah, are together.

"You wouldn't believe," Marilyn said, "how many people I know, from my days of living on the street. It is obvious to anyone what God has done for me."

Judy Ferguson is a free-lance writer who lives in Delta Junction.

What do you think? Forum Russia-Alaska